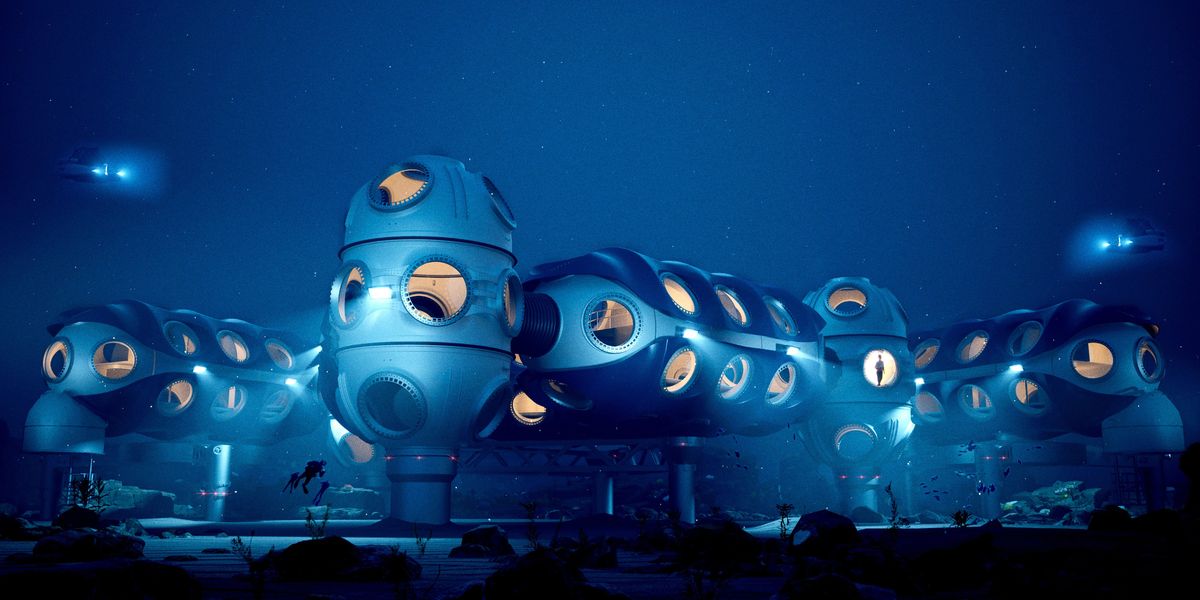

The future of people living in the sea takes shape in an abandoned quarry on the border of Wales and England. The Deep Ocean Research Organization has embarked on a multi-year quest there to allow scientists to live on the sea floor at depths of up to 200 meters for weeks, months and possibly years.

“Aquarius Reef Base in St. Croix was the last station installed in 1987, and not much has been breached there in the last 40 years,” says Kirk Krack, Deep’s human diver leader. “We’re trying to bring ocean science and engineering into the 21st century.”

Deep’s agenda has a significant milestone this year – the development and testing of a small modular environment called Vanguard. Able to house up to three divers for up to a week or so, this portable pressurized underwater shelter will be the stepping stone to a more permanent modular habitat system – known as Sentinel – due to go live in 2027. By 2030, we hope to see permanent human presence in the ocean,” says Krack. All this is now possible thanks to an advanced 3D printing and welding approach that can print these large residential structures.

How would such a presence benefit marine science? Krack crunches the numbers for me: “Dive at 150 to 200 meters at the same time, you can only work 10 minutes, followed by 6 hours of decompression. With our underwater habitats, we will be able to do seven years of work in 30 days with less decompression time. More than 90 percent of the ocean’s biodiversity lives 200 meters deep and on the coast, and we only know about 20 percent of it.” Understanding these underwater ecosystems and environments is a crucial piece of the climate puzzle, he adds: The oceans absorb nearly a quarter of human-caused carbon dioxide and roughly 90 percentage of excess heat generated by human activity.

Life under water is green this year

Deep aims to build an infrastructure to support underwater life that would include not only modular habitats but also training programs for the scientists who will use them. Living underwater for long periods involves a specialized type of activity called saturation diving, so called because the diver’s tissues become saturated with gases such as nitrogen or helium. It has been used for decades in the offshore oil and gas industries, but is uncommon in scientific diving, except for the relatively small number of researchers who have been lucky enough to spend time in Aquarius. Deep wants to make this standard procedure for underwater researchers.

First up the list is the Vanguard, a rapidly deployable, shipping-container-sized, expedition-style subsea station that can be transported and resupplied by ship and accommodates three people down to a depth of about 100 meters. It is due to be tested at a quarry outside Chepstow in Wales in the first quarter of 2025.

The plan is to deploy the Vanguard wherever it is needed for a week or so. Divers will be able to work on the seabed for hours before retiring to the pod for food and rest.

One of the new features of the Vanguard is its extraordinary power flexibility. There are currently three options: When located near the coast, it can connect by cable to an onshore distribution center using local renewable resources. Farther out at sea, it could draw on supplies from floating farms with renewable energy sources and fuel cells that would power the Vanguard via an umbilical connection, or it could be powered by an underwater energy storage system that contains multiple batteries that can be charged, retrieved, and moved via submarine cables.

The breathing gases will be located in external tanks on the seabed and will contain a mixture of oxygen and helium that will depend on the depth. In an emergency, saturated divers will not be able to swim to the surface without suffering a life-threatening case of decompression sickness. Thus, Vanguard, like the future Sentinel, will also have backup power sufficient to provide 96 hours of life support in an external, adjacent module on the seabed.

Data collected from Vanguard this year will help pave the way for Sentinel, which will consist of pods of various sizes and capabilities. These modules can even be set to different internal pressures so that different sections can perform different functions. For example, laboratories could be under local bathymetric pressure to analyze samples in their natural environment, but a 1-atm chamber could be set up next to them where submarines could dock and visitors could observe the habitat without having to deal with local pressure . .

As Deep sees it, a typical configuration would house six people – each with their own bedroom and bathroom. It would also have a suite of scientific equipment including full wet labs to carry out genetic analyses, saving days by not having to transport samples to the upper lab for analysis.

“By 2030, we hope to see a permanent human presence in the ocean,” says one of the main representatives of the project

The Sentinel configuration is designed to last a month before needing a top-up. Gases will be refueled via an umbilical from a surface buoy, and food, water and other supplies will be carried during scheduled crew changes every 28 days.

But people will be able to live in Sentinel for months, if not years. “Once you’re fed, it doesn’t matter if you’re there for six days or six years, but most people will be there for 28 days because of crew changes,” says Krack.

Where 3D printing and welding meet

It’s a very ambitious vision, and Deep has concluded that it can only be achieved with advanced manufacturing techniques. Deep’s manufacturing arm, Deep Manufacturing Labs (DML), has come up with an innovative approach to building the pressure hulls of habitat modules. It uses robots to combine additive metal fabrication with welding in a process known as wire arc additive manufacturing. With these robots, metal layers are created in the same way as 3D printing, but the layers are joined together by welding using a metal and inert gas torch.

At Deep’s base of operations at a former quarry in Tidenham, England, resources include two Triton 3300/3 MK II submarines. One of these is seen here in the Deep Quarry’s floating “island” dock. Deep

At Deep’s base of operations at a former quarry in Tidenham, England, resources include two Triton 3300/3 MK II submarines. One of these is seen here in the Deep Quarry’s floating “island” dock. Deep

During a tour of DML, Harry Thompson, head of advanced manufacturing engineering, says, “We sit in a gray area between welding and the additive process, so we follow the welding rules, but for the pressure vessels (we also) follow the stress-relief process that is applicable to the additive component. We also test all parts with non-destructive testing.”

Each of the robotic arms has an operating range of 2.8 x 3.2 meters, but DML has expanded this area with a concept it calls the Hexbot. It is based on six robotic arms programmed to work together to create habitat hulls up to 6.1 meters in diameter. The biggest challenge in creating hulls is controlling the heat during the additive process so that the parts don’t deform as they are created. For this, DML relies on the use of heat-resistant steels and very precisely optimized process parameters.

Technical challenges for long-term housing

production, there are other challenges unique to the tricky business of keeping people happy and alive 200 meters underwater. One of the most fascinating revolvers around helium. Because of its narcotic effect at high pressure, nitrogen should not be breathed by humans at depths below about 60 meters. So at 200 meters the breathing mixture in the biotope will be 2 percent oxygen and 98 percent helium. But because of its very high thermal conductivity, “we have to heat the helium to 31-32°C to get the normal internal ambient temperature of 21-22°C,” says Rick Goddard, Deep’s director of engineering. “This creates a humid atmosphere, so the porous materials become a breeding ground for mold.”

There are also a number of other material-related issues. The materials cannot release gases and must be acoustically insulating, light and structurally sound at high pressures.

Deep’s test sites are a former quarry in Tidenham, England, which has a maximum depth of 80 meters. Deep

Deep’s test sites are a former quarry in Tidenham, England, which has a maximum depth of 80 meters. Deep

There are also many electrical problems. “Helium will break certain electrical components with a high degree of certainty,” says Goddard. “We had to tear the device apart, replace the chips, change (the printed circuit boards) and even design our own non-gassing PCBs.”

The electrical system will also need to accommodate an energy mix with sources as diverse as floating solar farms and surface buoy fuel cells. Energy storage devices present major problems in electrical engineering: Helium penetrates capacitors and can destroy them when they try to escape during decompression. Also batteries have high pressure issues so they will need to be off site in 1 atmosphere pressure vessels or oil filled blocks to prevent differential pressure inside.

Is it possible to live in the ocean for months or years?

When you’re trying to be the SpaceX of the ocean, questions naturally arise about the feasibility of such an ambition. How likely is it that Deep will make it? At least one top author, John Clarke, is a believer. “I was impressed by the quality of engineering methods and expertise applied to the problems at hand, and I am excited about how DEEP is using new technologies,” says Clarke, who was the chief scientist for the US Navy’s Experimental Diving Unit. “They are going above and beyond… I am happy to support Deep in their quest to expand the human reach of the sea.”

From your articles

Related articles on the web