This sponsored article is brought to you by NYU Tandon School of Engineering.

In a major advance in drug delivery, researchers have developed a new technique that addresses an ongoing challenge: the scalable production of nanoparticles and microparticles. This innovation, led by Nathalie M. Pinkerton, assistant professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering at the NYU Tandon School of Engineering, promises to bridge the gap between laboratory drug delivery research and large-scale pharmaceutical manufacturing.

The breakthrough, known as sequential nanoprecipitation (SNaP), builds on existing nano-precipitation techniques and offers improved control and scalability, essential factors in ensuring that drug delivery technologies reach patients efficiently and effectively. This technique allows scientists to

produce drug-carrying particles that retain their structural and chemical integrity from laboratory settings to mass production– a crucial step to bringing new therapies to market.

Using 3D printing to overcome the drug distribution challenge

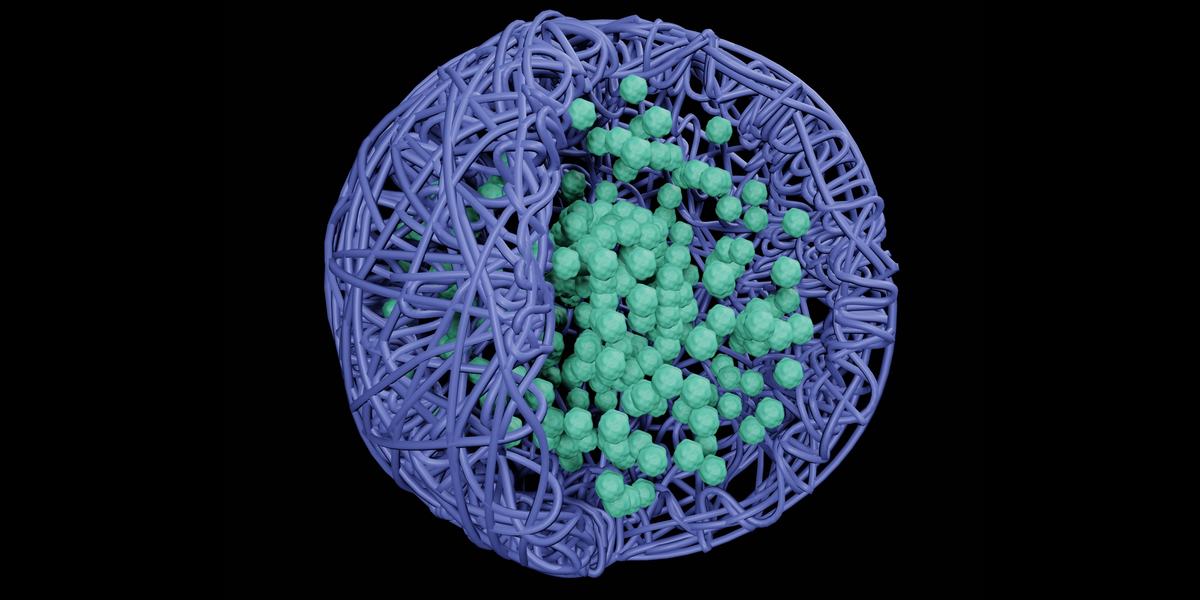

Nanoparticles and microparticles hold great promise for targeted drug delivery, enabling precise transport of drugs directly to disease sites while minimizing side effects. However, consistent production of these particles at scale has been a major hurdle in translating promising research into viable treatments. As Pinkerton explains: “One of the biggest hurdles in translating many of these precision medicines is manufacturing. With SNaP, we address this challenge head-on.

Traditional methods such as Flash Nano-Precipitation (FNP) have been successful in creating some types of nanoparticles, but often struggle to produce the larger particles that are necessary for certain delivery methods, such as inhalation. FNP creates core-shell polymer nanoparticles (NPs) ranging in size from 50 to 400 nanometers. The process involves mixing drug molecules and block copolymers (special molecules that help form particles) in a solvent, which is then rapidly mixed with water using special mixers. These mixers create small, controlled environments where particles can form quickly and uniformly.

Despite its success, FNP has some limitations: it cannot create stable particles larger than 400 nm, the maximum drug content is about 70 percent, the yield is low, and it can only work with very hydrophobic (water-repelling) molecules. These problems arise because particle nucleation and particle stabilization occur simultaneously in the FNP. The new SNaP process overcomes these limitations by separating the nucleation and stabilization steps.

There are two mixing steps in the SNaP process. First, the core components are mixed with water to start forming the core particles. A stabilizing agent is then added to stop nucleation and stabilize the particles. This second step must occur quickly, less than a few milliseconds after the first step, to control particle size and prevent aggregation. Current SNaP setups connect two dedicated mixers in series and control the delay time between steps. However, these setups face challenges, including high cost and difficulty in achieving the short lag times required for small particle generation.

A new approach using 3D printing has solved many of these problems. Advances in 3D printing technology now make it possible to create the precise, narrow channels needed for these mixers. The new design eliminates the need for external hoses between each step, allowing for shorter lag times and preventing leaks. The innovative stackable blender design combines two blenders into a single setup, making the process more efficient and user-friendly.

“One of the biggest barriers to translation for many of these precision medicines is manufacturing. With SNaP, we address this challenge head-on.

—Nathalie M. Pinkerton, NYU Tandon

Using this new SNaP mixer design, the researchers successfully created a wide variety of nanoparticles and microparticles loaded with rubrene (a fluorescent dye) and cinnarizine (a weakly hydrophobic drug used to treat nausea and vomiting). This is the first time that small nanoparticles below 200 nm and microparticles have been produced using SNaP. The new setup also demonstrated the critical importance of the lag time between the two mixing steps in controlling particle size. This delay time control allows researchers access to a larger range of particle sizes. In addition, Pinkerton’s team achieved the successful encapsulation of both hydrophobic and weakly hydrophobic drugs into nanoparticles and microparticles using SNaP for the first time.

Democratization of access to cutting edge techniques

The SNaP process is not only innovative, but also offers a unique practicality that democratizes access to this technology. “We’re sharing the design of our mixers and showing that they can be 3D printed,” says Pinkerton. “This approach allows academic labs and even small industrial players to experiment with these techniques without investing in expensive equipment.”

Schematic of a layered mixer with an inlet stage for syringe attachment (top) directly connected to the first mixing stage (middle). The first mixing stage is interchangeable, with either a 2-inlet or 4-inlet mixer depending on the desired particle size regime (punctate antisolvent streams are only present in the 4-inlet mixer). This stage also contains a passage for the streams used in the second mixing step. All streams are mixed in the second mixing stage (bottom) and exit the device.

Schematic of a layered mixer with an inlet stage for syringe attachment (top) directly connected to the first mixing stage (middle). The first mixing stage is interchangeable, with either a 2-inlet or 4-inlet mixer depending on the desired particle size regime (punctate antisolvent streams are only present in the 4-inlet mixer). This stage also contains a passage for the streams used in the second mixing step. All streams are mixed in the second mixing stage (bottom) and exit the device.

The availability of SNaP technology could accelerate progress in drug delivery and allow more researchers and companies to use nanoparticles and microparticles in the development of new therapies.

The SNaP project is an example of a successful interdisciplinary effort. Pinkerton emphasized the diversity of the team, which included experts in mechanical and process engineering as well as chemical engineering. “It was a truly interdisciplinary project,” she noted, noting that the contributions of all team members—from undergraduate students to postdoctoral researchers—were essential to bringing the technology to life.

In addition to this breakthrough, Pinkerton envisions SNaP as part of its broader mission to develop universal drug delivery systems that could ultimately transform healthcare by enabling versatile, scalable, and customizable drug delivery solutions.

From industry to academia: a passion for innovation

Before coming to NYU Tandon, Pinkerton spent three years in the oncology research division of Pfizer, where she developed novel nanomedicines for the treatment of solid tumors. The experience, he says, was invaluable. “Working in industry gives you a real-world view of what’s possible,” he points out. “The goal is to do translational research, meaning it ‘translates’ from the lab bench to the patient’s bedside.”

Pinkerton, who earned a BS in chemical engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2008) and a PhD in chemical and biological engineering from Princeton University, was drawn to NYU Tandon in part because of the opportunity to collaborate with researchers across the country. NYU ecosystem, with which he hopes to develop new nanomaterials that can be used for controlled drug delivery and other biological applications.

She also came to academia for her love of learning. At Pfizer, she realized her desire to mentor students and pursue innovative interdisciplinary research. “Here, students want to be engineers; they want to make a difference in the world,” she reflected.

Her team at Pinkerton Research Group focuses on the development of sensitive soft materials for biological applications, from controlled drug delivery to vaccines to medical imaging. They take an interdisciplinary approach and use tools from chemical and materials engineering, nanotechnology, chemistry and biology to create soft materials using scalable synthetic processes. They focus on understanding how process parameters control the final properties of the material and, in turn, how the material behaves in biological systems—the ultimate goal being a universal drug delivery platform that improves health outcomes in diseases and disorders.

Its SNaP technology represents a promising new direction in the quest to efficiently scale drug delivery solutions. By controlling assembly processes with millisecond precision, this method opens the door to creating increasingly complex particle architectures that provide a scalable approach for future medical advances.

The future is bright for the drug delivery field as SNaP paves the way for an era of more accessible, adaptable and scalable solutions.