We are all used to sensationalist headlines about some disaster on the horizon. So I don’t blame anyone who was exhausted when they saw dozens of scientists warning in the journal last month Science that mirror bacteria could cause catastrophic ecosystem collapse and even mass extinction.

After all, we already have looming threats like H5N1 to worry about, and more generally, we live in an age where, as Adam Kirsch recently said in The Atlantic, it feels like “the apocalypse, all the time”. News of the mirror bacteria hit the same week we were told that a widely read study about how our black spatulas are killing us was actually just the result of a math error. It can be hard to tell which concerns are deadly serious and which are just headlines that will be forgotten a month later.

But after reading a lot more about the mirror bacteria situation, I’m here with the bad news: It’s real, and it’s really serious.

More than 35 scientists, including leading researchers across half a dozen different disciplines, came together in a December technical report to argue that continued work on mirror bacteria could trigger mass extinctions. The catastrophe it warns of is plausible, if staggering.

And it’s not one of those situations where the skeptics come from outside: Many of the leading scientists who worked on the invention of mirror life are now convinced that such work would be incredibly dangerous. In fact, it’s one of the few cases where experts have become more interested because they’ve learned more, instead of having less.

But there is also good news: Now that we are aware of the risk, disaster should not happen by accident. At this point, mirror life is largely theoretical – it would take decades of work to actually create it. So when scientists focus more closely on the risks, they can stop this work at very little cost to the additional necessary research.

And with scientists from many fields voicing their concerns, there’s a good chance we as a world will agree on the right things and just not go there. Which is ideally how we should handle new existential risks.

Imagine the letter R and its mirror image, the letter Я. No matter how much you spin the letter R on a two-dimensional page, you will never get Я. If you make a protein to attach to R, Я won’t fit, and the molecule will turn out differently if it uses R or Я as a backbone.

Register here to explore the big and complicated problems facing the world and the most effective ways to solve them. Sent twice a week.

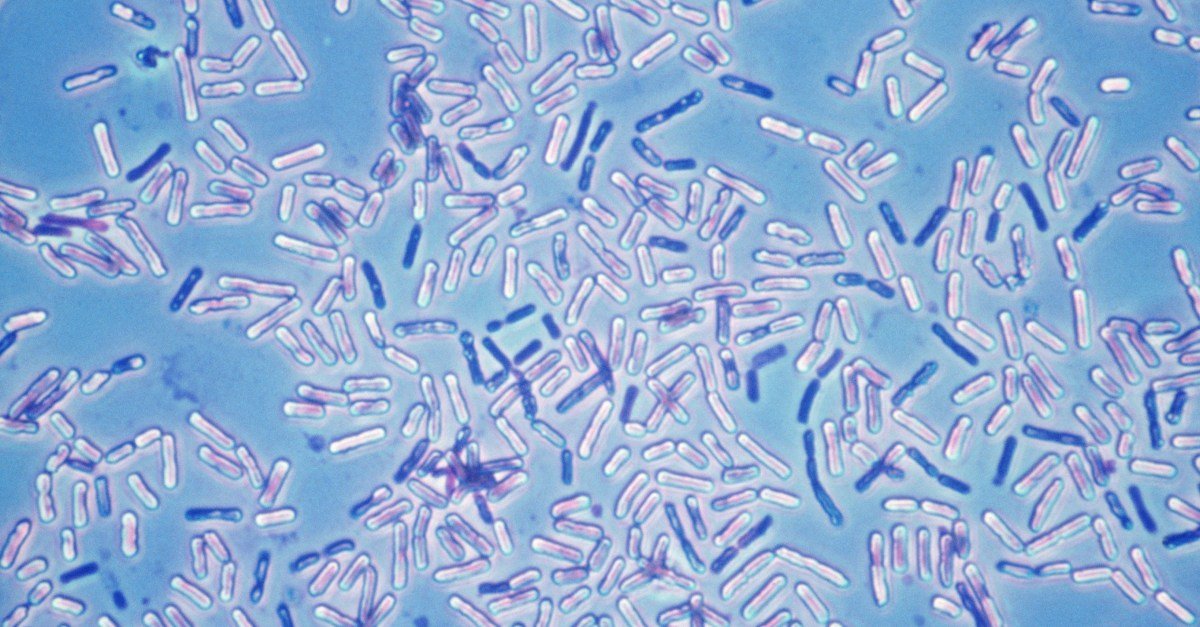

This is the basic concept of mirror life, albeit in three dimensions rather than two. The amino acids that make up the proteins that make up all life on Earth can form from atoms in two different mirror-image ways, the colloquially “left” and “right” forms. But while molecules come in both forms, all life on Earth makes proteins only from left-handed amino acids (and most other biomolecules, like DNA, also come with an “arm” – that’s why DNA’s spiral helix always goes in one direction.)

This presents an exciting scientific puzzle: Couldn’t you, in principle, assemble “mirror life”—life made from right-handed amino acids? It would be a huge engineering project, involving work that we cannot yet do.

But in principle it should be possible. We have already created mirror proteins and mirror enzymes that can read mirror genes.

What could go wrong?

The question is what would happen after you manage to build a mirror life.

At first, mirror bacteria were thought to be effectively harmless because they could not digest most of the “normal” molecules that make up all existing life. Sure, they could eat simple nutrients that don’t have the “handiness” property. But would that be enough for them to multiply and spread?

Many scientists initially assumed that this would not be the case, meaning that mirror life would be safely self-limiting, unable to spread very far as it would be unable to consume the rest of life, including human beings.

But as they studied this possibility further, experts began to worry that this was not true. “Contrary to previous discussions of mirror life, we also realized that general heterotrophic mirror bacteria could find a variety of nutrients in animal hosts and the environment, and therefore would not be intrinsically biologically contained. Science message found.

So the mirror bacteria would eventually be able to find enough to eat. Even worse, the existing life would try to eat them. This means that creating mirror bacteria could be something like introducing an invasive species into an ecosystem (in this case, an entire planet) where it has no predators.

Without initially developing something to eat or counter it, it could probably spread quickly. Invasive species can be very difficult to eradicate, even if they do not reach very high populations. Mirror bacteria could be just that: a new species of globally widespread environmental bacteria alongside many existing ones.

But how catastrophic would the introduction of this new invasive species be? Humans (and other animals and plants) are exposed to environmental bacteria all the time, and these are usually not a problem unless, for example, you have a compromised immune system.

So a team of immunologists worked on the question of whether our immune system would respond correctly to the invasion of mirror bacteria. Disturbingly, they concluded that probably not.

While some of our immune defenses work without any specific targeting of a particular pathogen, many of them only work by locking onto the invading pathogen – something we wouldn’t be able to do with mirror bacteria. And scientists haven’t just discovered that it can make people sick. It could work for exactly the same reason everything else diseased – any animal, even plants, can be vulnerable (although there would be considerable variation in exactly how susceptible any species would be).

The result according to the December report in Scienceit could be scary.

“We cannot rule out a scenario in which the mirror bacterium behaves as an invasive species in many ecosystems and causes ubiquitous lethal infections in a substantial proportion of plant and animal species, including humans,” the authors found, adding that the likely outcome is: unprecedented and irreversible damage.

“It is difficult to overestimate how serious these risks may be,” cautioned immunologist Ruslan Medzhitov, one of the technical report’s co-authors, in a statement sent to me. “Living in an area contaminated with specular bacteria could be similar to living with severe immunodeficiencies: Any exposure to contaminated dust or soil could be fatal.”

“We Won’t Do It”

To be clear, there were many good reasons to consider creating mirror life. “It’s naturally incredibly cool,” Kate Adamala, a synthetic biologist at the University of Minnesota, told the New York Times about the effort to create the mirror bacteria. “If we were to create a mirror cell, we would create a second tree of life.

Indeed, Adamala and three other scientific colleagues are the recipients of a 2019 grant in which they explained that they are “pursuing the design, engineering and safe deployment of synthetic mirror cells.” But as they looked into it more, collaborating on a 299-page technical report, she and her colleagues became convinced that it just wasn’t worth it: All four have now joined the challenge. Science to stop work. “We’re saying, ‘We’re not going to do it,'” Adamala told the Times.

The US government, which funded the work of Adamala and her colleagues to build mirror life, is also adapting in response to this warning.

“We appreciate the efforts of these scientists to identify and assess the potential future risks of this type of synthetic organism, … Advances in the life sciences and related technologies are now enabling scientists in ways that were hardly imaginable just a few decades ago,” a company spokesperson told the Office of Scientific and technology policy of the White House.

“These advances have remarkable potential for benefit and, as these scientists have made clear, also the potential for significant harm. Given the potential risks, we will work with and across the global research community to avoid and mitigate risks while protecting the potential benefits of research in other applications of synthetic biology. The US government is launching an advisory process to review scientific assessments of the implications of mirror life and develop or revise appropriate federal biosecurity policy as needed.

For that reason, I think it can’t be read as a doom and gloom headline to start the year, but as a hopeful story. A huge number of talented people from various relevant fields came together and tried to figure out if there was a problem. They discovered it existed and changed course.

Of course, it is too early to declare victory. But if it’s a story of a looming challenge, it’s also a story of people rising to it—long before any disaster could strike.

A version of this story originally appeared in the Future Perfect newsletter. Register here!